Scalpel, Please — The Robot Will See You Now

002: Welcome to the start of the show

“Poor is the pupil who does not surpass his master.”

― Leonardo Da Vinci

The First Cut

Good morning.

Self-checkouts didn’t ask for permission. They just showed up—and cashiers disappeared. Do you think anyone thought they’d be replaced by a machine?

Now AI is creeping into everything: code, copy, classrooms. And yes—even the OR.

This week, we’re cutting into the rise of surgical automation, revisiting a surgeon who once crossed

species—and ethical lines—in pursuit of a breakthrough, and scanning the latest in medical news and

tech. We’ll end on a lighter note—because even in the sterile field, humor survives.

We’ve always said, “healthcare will never go away.”

But does that mean we won’t?

Let’s Scrub In.

Prepped & Draped

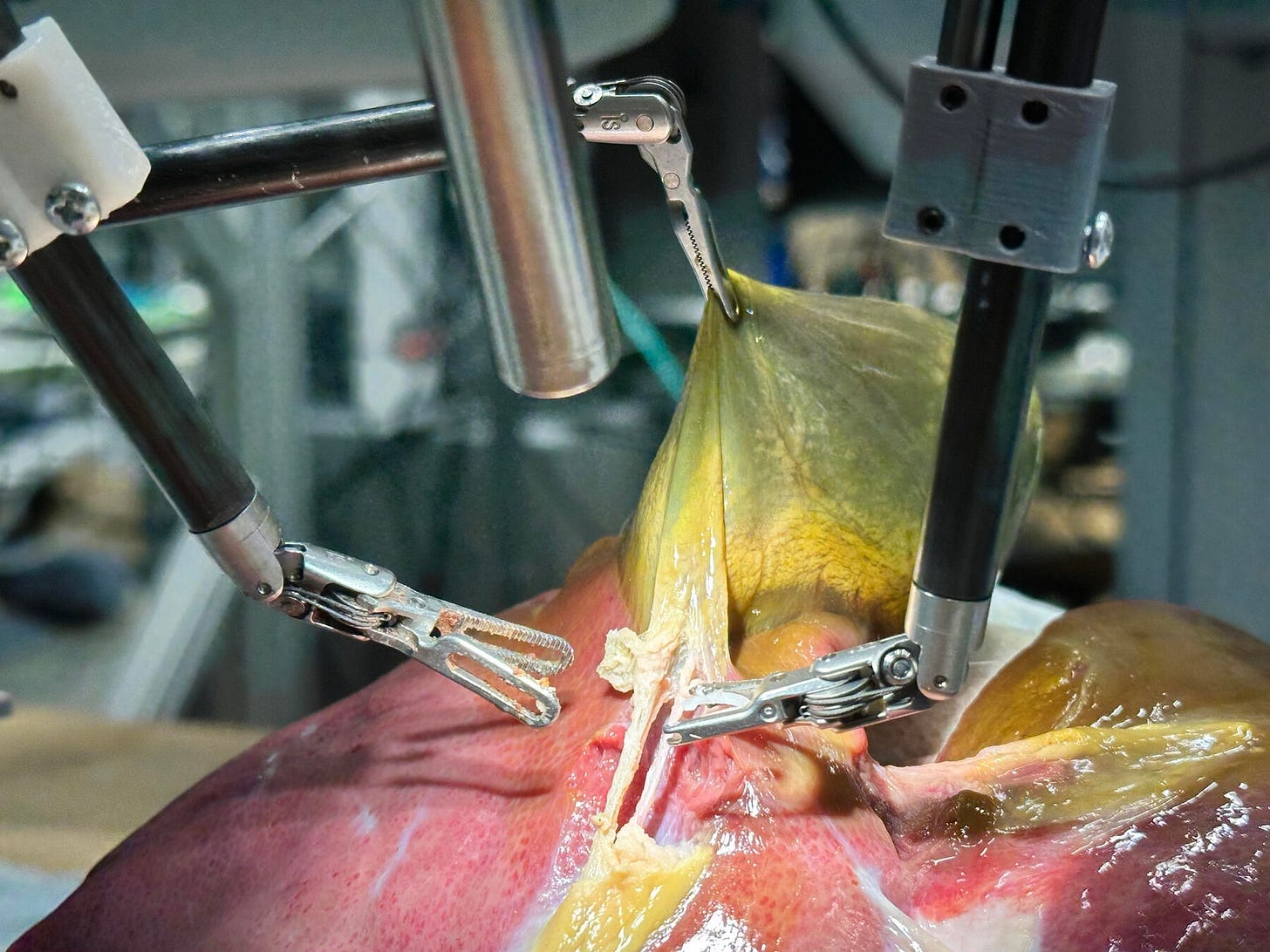

In 2022, Axel Krieger and his team at Johns Hopkins unveiled STAR — the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot — which successfully performed autonomous laparoscopic surgery on a live pig in a tightly controlled, pre-planned setting.

By 2024, at the Conference on Robot Learning in Munich, researchers from Johns Hopkins and Stanford showcased the next leap: a da Vinci robot trained with imitation learning and ChatGPT’s backend. After studying hundreds of real surgical videos, it mastered core tasks like lifting tissue and suturing. “A significant step forward toward a new frontier in medical robotics,” Krieger said.

He wasn’t bluffing.

By July 2025, Krieger’s team debuted the SRT-H — the Surgical Robot Transformer-Hierarchical — designed to perform an ex-vivo cholecystectomy with full autonomy. The robot learned by watching videos of Johns Hopkins surgeons remove gallbladders from pig cadavers, reinforced with task-specific captions outlining the procedure’s 17 key steps.

Though slower than a human — not unlike a surgical resident finding their footing — the robot successfully performed an ex-vivo cholecystectomy with 100% accuracy. More impressively, it adapted in real time to deliberately introduced challenges: anatomical variations, blood-like dyes, and shifting start positions.

Personally, I think this is a great feat — and incredibly scary interesting. The team at Johns Hopkins plans to test the model on more types of surgeries but stresses that “the real test will be how safely and effectively the findings of this study can be translated into human trials.”

The Mayo Memo

The Table-Mounted Titan

Dr. John Bookwalter, who passed in May at age 89, gave surgery one of its most reliable workhorses: the Bookwalter retractor. It’s not just a retractor — it’s an extra set of hands, a battlefield scaffold, and a fixture in major cases. If you've ever wrestled with the post or fumbled with the rings, you’re part of his legacy.

For those in the field — or those who may find themselves there someday — remember: every individual piece of the Bookwalter (or any retractor system) must be counted. It’s not just protocol; it’s protection against RSIs (retained surgical instruments), one of the most preventable yet devastating surgical errors.

Here is a great video breakdown discussing counting and assembly

Past in Practice

While scrolling through famousbirthdays.com, I stumbled upon a man named James D. Hardy.

He was an American surgeon who performed the first successful lung transplant in 1963 at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. The patient, John Russell, made the case even more complex—he was serving a life sentence for murder at the time of his admission.

Hardy never spoke directly with Russell about his sentence, but state officials were contacted behind the scenes, suggesting they might look favorably on commuting it if Russell chose to “contribute to human progress in this way.” He died eighteen days later.

Hardy was a man of surgical firsts—and controversy.

Following his lung transplant milestone, he set out to attempt the first heart transplant. But this wasn’t the kind of transplant you’re likely imagining.

In the early 1960s, a handful of surgeons had transplanted chimpanzee kidneys into thirteen human patients—a bizarre but oddly encouraging precedent. Inspired by this, Hardy acquired four chimpanzees to keep on standby.

Then, in 1964, a patient named Boyd Rush was transferred to Hardy’s team after being found with a faint pulse. His stepsister signed a broad, open-ended consent form that read:

“I agree to the insertion of a suitable heart transplant if such should be available at the time.”

As Rush’s condition deteriorated, a trauma patient in the ICU—diagnosed as brain dead—was identified as a potential heart donor. But brain death was not legally recognized at the time, and using that heart could’ve triggered serious legal consequences, since the donor’s heart was still beating.

The Vote in the OR

Hardy convened his team in the operating room. He polled them:

One assistant abstained.

One gave a firm yes.

Two others nodded quietly.

The consensus—barely there—was enough. With the legal option off the table, Hardy proceeded with his backup plan.

He transplanted the heart of a chimpanzee into Boyd Rush.

It began to beat. And continued—for about an hour.

The aftermath was brutal. Hardy was met with “icy disdain” from colleagues, and his institution faced sharp public criticism. What had been a bold experiment in xenotransplantation was viewed instead as a reckless, premature leap.

Yet Hardy had moved the line of possibility forward. Three years later, South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard would perform the first successful human-to-human heart transplant—a moment that redefined modern cardiac surgery.

Hardy’s legacy is complicated. But it’s also a reminder that the frontiers of medicine are rarely advanced without discomfort, doubt, and an uncomfortable kind of courage.

Rounds Report

Prairie Dogs Plead the Fifth in Arizona Plague Case

A Coconino County resident has died from pneumonic plague, likely linked to infected fleas carried by prairie dogs. Human-to-human spread is rare, but the desert’s looking a little more medieval this week. 🔗 Read More

Surgery Meets Sleep: New Tech Targets Apnea at the Source

CHI Health is implanting a pacemaker-like device to treat obstructive sleep apnea by stimulating airway muscles during sleep. For some, it could mean ditching the mask for good. 🔗 Read More

A Mother’s Mission Turns Grief Into Action

Massachusetts State Representative Kate Donaghue is channeling personal loss into public service, pushing for stronger substance use education and prevention after losing her son. 🔗 Read More

The Second Count

Raytecs? 7-8-9-10. That’s all for today — thanks for scrubbing in.

Stay sharp, stay curious, and above all: don’t lose track of your instruments (or yourself).

Check below for what is on the docket for Thursday as well as some information on how you could save a life.

Case to Follow

On Thursday: Consumer wearables, job market outlooks, crazy headlines and much more!

Would You Carry Narcan?

Overdoses can happen anywhere — in a bathroom stall, at a concert, on your commute. Carrying Narcan (naloxone) is one of the simplest ways to be prepared to save a life. It's safe, easy to use, and legal to carry in all 50 states.

If you're interested in getting Narcan for free, check out Next Distro. Fill out a quick questionnaire and have nasal naloxone sent to your door, for free

Disclaimer: This newsletter is intended for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The content is not a substitute for professional medical judgment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider before making medical decisions or taking action based on any information provided here.

I have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. I do not receive compensation, honoraria, consulting fees, or any form of industry support related to the content shared. All opinions expressed are my own and do not represent any employer, institution, or affiliated organization. If for whatever reason that were to change, they will be disclosed at the end of each publication. Thank you.